2008

Exhibition Das Böse ist ein Eichhörnchen, District Court Leipzig 2009

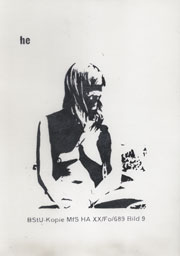

The installation Annunciation reconstructs in an associative form the moment when Alba D’Urbano - unknowingly - encountered a convolute of images held by the Ministry for State Security. Furthermore, the transformation of the (exemplary) “cover image” from a keepsake photograph to a piece of art is brought into focus by Alba D’Urbano's drawings. These consolidate a further appropriation of the “portrait” of Tina Bara which had been used by Dora Garcia. In turn, these portraits become part of an installation that locates the formerly private image in the context of archives, while their function remains unclear. Shelf parts and folders seem to be torn out of context. Besides these drawings and a text, the folders are filled with blank papers – projection surfaces for the millions of photographs, texts, and data that had been fed into the surveillance system as substantial information about forces “working against the state”. In a kind of poetically charged protocolary analysis, the text by Alba D’Urbano describes her first encounter with the photographs at the Museum of Contemporary Art Leipzig.

|

Minutes from memory – Excerpts Dora Garcia, Pictures at an exhibition

Leaders of the excursion: Alba D’Urbano, professor; Franz Alken, assistant; Intermedia class of the HGB Wächterstr.11, Leipzig Place: Museum of Contemporary Art Leipzig (GfZK), Karl Tauchnitz Str. 9–11, Leipzig Participants: Reiko Kammer, Julia Sing, Luise Hennig, Susanne Kaiser, Stefan Hurtig, Carolin Weinert, Lena Brüggemann. Guided tour through the exhibition: “Zimmer, Gespräche” by Dora Garcia Curator: Julia Schäfer

Minutes recorded by: Alba D’Urbano Minutes, begun July 2007 in Leipzig, revision, completed September 2008, in Fiskars (FIN).

As part of the class activities, which include lectures, class meetings, individual consultations, as well as excursions and exhibition visits, we went to see the exhibition “Zimmer, Gespräche” (“Rooms, Conversations”) by Dora Garcìa at the Museum of Contemporary Art Leipzig in summer semester 2007. Our visit to this exhibition was intended to deepen the research activities for the project “Absolut Böse” (“Utterly Evil”), a topic-centered exhibition project organised by Franz Alken and myself, in which HGB students were working interdisciplinary across classes. To us, visiting the exhibition “Zimmer, Gespräche” was of interest because it artistically explored some of the topics of the project – such as themes of surveillance, control, and power – in connection with the more recent history of the German state. (...) The meeting point for the group was the entrance of the “new” GfZK building which is close to our academy. (...) A man and a woman, employees of the gallery, were sitting at two different locations in the upper part of the space, which is elevated like a platform and positioned to the left of the entrance door. (...) The woman would often look in our direction and was attentively typing sentences into her computer. (...) Bright, piercing sunlight fell on the bulkily suspended designer shelves, as I let my gaze pan from the writing woman to the outside. The street was empty, only a bus from line 89 was driving slowly past the trees of Johanna Park opposite the gallery, a romantic image – a peculiar, moving metaphor of German history. Questions about the randomness of these events subtly crossed the fragile membranes of my brain cells and fused with some more deeply stored thoughts: the origin of the name of this bus line from the post-Reunification era again and again briefly occupies my thoughts, often only for a few seconds, then it disappears without a trace: no time to engage in an in-depth research... no answer. (...) The film projection must be considered the core of the exhibition, both in terms of its content and the way in which it extends across the space, J.S. explained. The dramaturgy, the narrative thread of the exhibition do however spread across all the other rooms of the gallery: like satellites the other media documents orbit the hub of light and projection, and are illuminated by its radiance and fictionality. The satellites consist of found photo and video materials selected by the artist from the archives of the Ministry for State Security, appropriated and presented as “ready mades”. (...) The students look a little irritated, (...) until a voice, slightly louder, made itself heard and returned the confused looks of the others with an intelligible language. It is widely known that it is very difficult to access archive material of the former Ministry for State Security and that images from these archives may only be published with the consent of the people depicted. The legacy of the Ministry for State Security is managed by the BStU (Office of the Federal Commissioner Preserving the Records of the Ministry for State Security of the former GDR), in particular the release of photographic and film material from the heaps of stored images is strictly administered; the protection of personal rights is often considered as paramount, so that only the persons affected or scientists who can prove that they conduct research in this field are allowed access to the files – often only after preparing repeated and complicated written requests. How was it possible that such material was handed over to the artist for the production of “ready mades”, the voice asked. Even to fill an entire exhibition with them, I thought nodding... (...)

In the adjoining room we saw four video projection surfaces suspended from the ceiling, which divided the room diagonally into two parts. Placed behind each other as in a sequence and altered according to similar principles, the video images projected here show people who have been captured in very different situations: out on the street or in private interiors, in urban surroundings or on lonely dirt roads... Very different atmospheres and actions, which are coordinated and appear to follow a crime-novel dramaturgy: night shots, cars driving. A couple meet... The inferior quality of the footage betrays their origin. An oppressive mood emerges in the fluttering twilight of the exhibition space, the viewer is undoubtedly forced into the position of a voyeur, in the position of those who had previously produced these pictures in secret and later evaluated them. The visitors to the exhibition become witnesses and at the same time partners in crime, accomplices to a system, a historic process, that spits these images out from the machinery of production back then into the use in an art context today. The impressions of an “illegal,” an “immoral” participation lurks among us: we look at the “classified” image material, we observe people who might have done something illegal. Stolen images were stolen one more time, prepared for the art context and presented in a “white cube”. (...) Someone asked J. S. to explain the artist’s strategies of appropriation in more detail. The question about the source of these images was also put forward once more by the students: where do they originally come from, who are the people behind the camera, and, even more importantly, who are the people watched and observed, the victims of a totalitarian system. What has become of these people? The terrifying idea that some of them might have already died. Perhaps they had managed to escape the country once and for all. One is only familiar with the stories of the more popular cases, but what about the others: failed due to the political system, due to the consequences of persecution, to age. Do they have a job, are they still alive? Or have they, which seems to be the most probable assumption, successfully changed into “normal” citizens of our consumer society? The question about the fates of these people was very appealing to me. This tiny, incidental piece of their past, which was offered to me in the form of moving images at this exhibition, moved me. What did become of the “walking couple”? Were they in love? Were they just friends? Did they suffer? And that woman, walking alone along the road as in a dreamy winter landscape, where does she go to, where does she come from? Why was the human act of walking – an activity, that billions of people all across the world ceaselessly engage in – worthwhile for storage by the Ministry for State Security? And what had happened, once the camera had been switched off? (...) Afterwards we entered a room washed in light, where some groups of black/white photos were hanging on the walls at eye level. (...) My attention was drawn to a sequence of pictures that were hanging on the right-hand wall, they were portraits, group shots respectively, taken in an outside setting. The photos created a mood of cheerful togetherness, communicative moments, joy perhaps... The people portrayed were almost exclusively of a young age, and all of them women. Their bodies are naked, they are close together, framed by plants and baskets: a jaunt, I thought. As well, the effort to anonymise the images had been thoroughly executed in these pictures, in a well-behaved and orderly way. I could imagine those hands, as they carefully covered the eyes of the young women with small, square veils... a reversal of the Chador principle, a reversal of the way censorship usually works: not the nude body parts had been covered, but the eyes; in a remarkable way the black bars had emigrated from the erogenous areas of the body to the faces: with astonishment my mind associated this type of censorship with the black rectangles that cover the primary genitals in pornographic images... (...) The male or female “author” of the intervention at hand seemed to have followed a conceptual principle. Lined up next to each other, the short black bars gain a decorative character. I was wondering if this intervention, if the migration of the bars had been initiated by the artist or by the federal office. (...) The title of the images “Women, naturist meeting, end of the seventies” gives only a very general information about them. (...) The transparency of the glass wall gave opportunity to let one's gaze wander on to the entrance hall, a pleasant reunion soothed the sense of unease, that the exhibition had left as a trace on our psychic condition. The woman at the reception desk looked again in our direction, smiled and continued her writing, still... again and again... Time appeared to stand still in this space, mixed with the air and the light that brought the world outside to us through the door of the gallery. In the background I could still hear the words of J. S.; they prompted me, like Orpheus in the land of the dead, to turn around. Behind me she was still speaking to my students. In the meantime the group had moved to another work, the students were looking at a text that was projected on the wall. The text was changing, words were continually written... J. S. explained to us that this text was being created in “real time”, so to say. Fiction and reality coincided in this moment and fled away from me, like Eurydice, my mirror image... We were slightly shocked when we realised that the words that were writing themselves on the wall were in fact de-scriptions of our clothes, our bodies and our actions... We realised that we had become an unaware, “watched” part of a theatre performance: “Instant Narrative” is the title of the piece, J.S. said. The artist had hired an author, who was sitting at the reception, to write down everything that occurred at the entry of the museum, a mode of surveillance that had also been practised by the Ministry for State Security. The texts appear poetical, the artist will collect the texts and edit them later... I felt baffled and naked after this discovery – the feeling that the artist had gone a little too far; the impression that she had been playing Ministry for State Security with us... Unable to decide whether I found the exhibition to be brilliant or outrageous, and impressed both positively and negatively at the same time, I gratefully took my feeling of unease and the book of the exhibition, which J. S. offered to me as a present, with me. On the cover was the picture of a young woman, naked – good sales policy – I thought: a “Cover Girl”.... |

Installation: 1 text, 4 drawings, shelf, 15 folders

Size: 151 x 133,5 x 32 cm